The Context Behind Oruam’s Dazed Cover They Didn’t Tell You

A murdered journalist. A drug empire. A fashion spread in red. What gets erased when style skips the story.

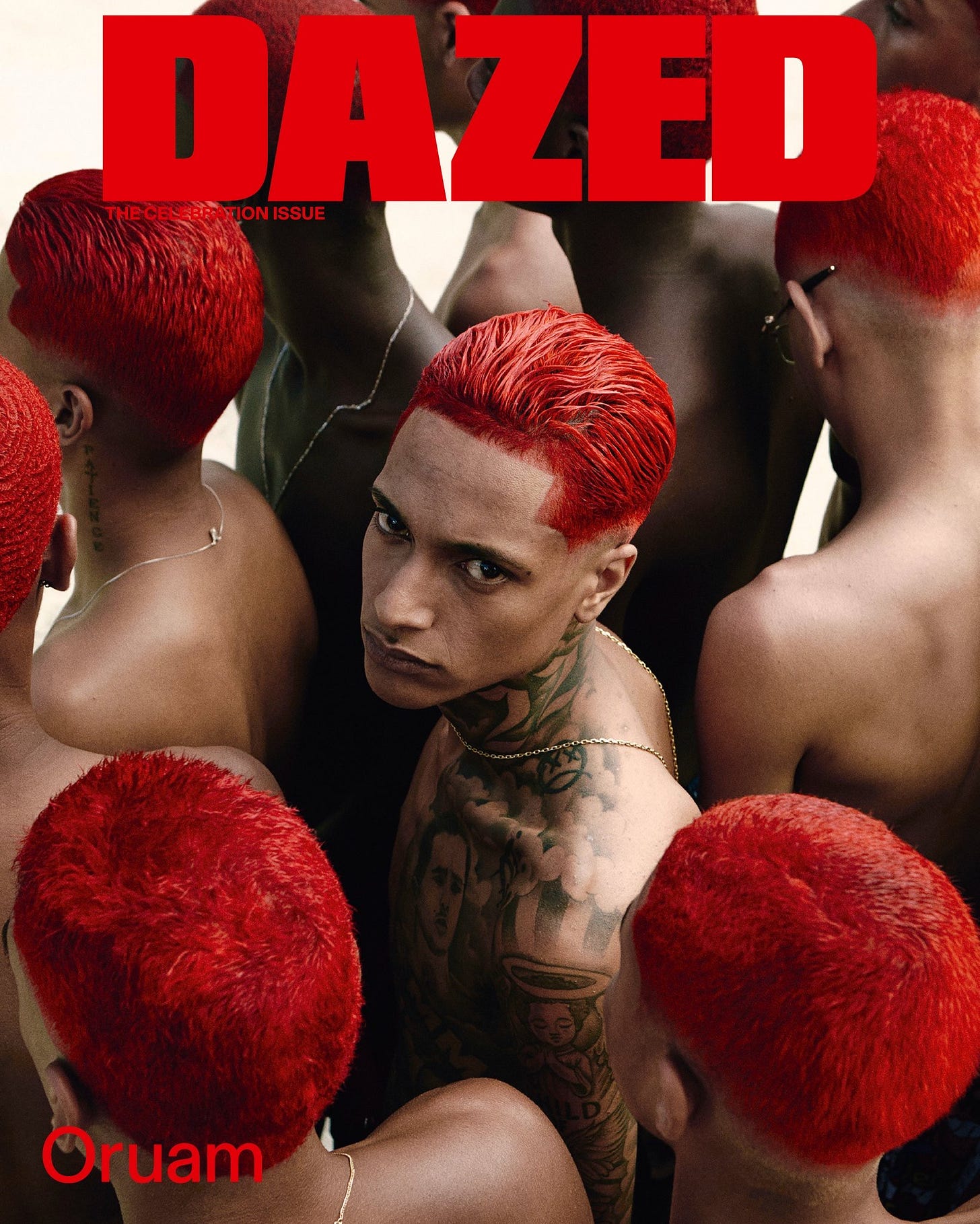

This week, Dazed released its latest cover star: Oruam, a rising Brazilian rapper styled as the face of global Gen Z rebellion. Shirtless, tattooed, and gazing into the camera with practiced disaffection, he fits the new archetype of the international star: one foot in street authenticity, the other in avant-garde fashion. But if you saw the cover and thought, he looks cool, you’re not wrong, you’re just missing the part the editorial left out.

Because Oruam isn’t just a rapper. He’s the son of one of Brazil’s most notorious crime bosses, and his very existence is a lightning rod for Brazil’s ongoing fight over the aesthetics of violence, the politics of memory, and the cultural laundering of organized crime. The photos might be fire but the backstory? Not so much.

The Bloodline

Oruam (real name: Mauro Davi dos Santos Nepomuceno ) is the son of Marcinho VP, a historic leader of Comando Vermelho (Red Command), Brazil’s oldest and once most powerful drug trafficking organization. Formed in the 1970s in Rio’s prison system, partly as a response to military dictatorship repression and partly as a collective between common criminals and leftist revolutionaries, Comando Vermelho evolved into a sprawling network of drug trafficking, arms dealing, extortion, and street-level warfare. It helped invent the modern Brazilian favela drug war.

Marcinho VP, now imprisoned, became infamous in the late 1990s and early 2000s for overseeing vast portions of Rio’s cocaine trade and orchestrating armed territorial control of entire favelas. He’s been linked to homicides, kidnappings, and mass violence. He is not a shadowy figure from Oruam’s distant past, he’s Oruam’s father. And Oruam has made no effort to distance himself from that lineage. In fact, he’s worn shirts calling for his father’s release, refers to him with open pride in interviews and visits 3 times a year.

The Uncle

Even more explosive is Oruam’s tribute to his godfather, Elias Maluco (real name: Elias Pereira da Silva), another high-ranking Comando Vermelho leader. In 2002, Maluco ordered the kidnapping and brutal murder of journalist Tim Lopes, who was working undercover for TV Globo to expose child exploitation and drug-fueled “funk parties” in the Vila Cruzeiro favela.

Lopes was abducted by gang members, taken to the nearby Favela da Grota, tortured, his eyes burned with cigarettes, then dismembered alive and set on fire inside a stack of tires doused with gasoline. This method of execution is locally called “micro-ondas” or “microwave.” The case horrified the nation and galvanized international criticism of Brazil’s inability to protect journalists.

Oruam has a tattoo of Elias on his body and has referred to him as his “uncle at heart.” When asked about it, he doubled down, saying: “I don’t look at the error when it’s someone I love.”

Imagine an American rapper sporting a tattoo of Whitey Bulger or Pablo Escobar and then going on a press tour in Vogueor Rolling Stone without ever being asked to explain it. That’s the level of surreal silence happening here.

The Performance, the Protest, the Fallout

At Lollapalooza Brazil in 2024, Oruam stepped on stage wearing a shirt that read “Liberdade” with a photo of his fathers face on it. It was more than a fashion statement. It was a direct provocation, one that enraged lawmakers, victims’ families, and the Brazilian public. In response, a group of politicians proposed the “Lei Anti-Oruam”(Anti-Oruam Law), a bill that would block public funding and government support for artists who glorify or have familial ties to organized crime.

The backlash also reopened debates about Brazil’s celebrity-crime-industrial complex, where pop culture, fashion, and criminality often blur. In a country with deep inequality and a long history of state abandonment, figures like Oruam occupy a strange space, both celebrated as self-made success stories and criticized for romanticizing the very violence that keeps so many in poverty.

Dazed and Disconnected

And then Dazed dropped the cover devoid of any of this context. No mention of Comando Vermelho, no footnote on Tim Lopes, and the only nod to the Anti-Oruam Law was with a quote from Oruam, “There’s a bill project with my name, so I’m really famous. They will remember me forever.”

And it’s not lost on me that Dazed shot Oruam’s cover in bold, aggressive red, the unmistakable signature color of Comando Vermelho, the drug faction his father helped lead. Whether intentional or an unfortunate coincidence, it reads like a wink to insiders and a red flag to anyone paying attention.

But context isn’t a distraction, it’s the story. And when that story involves a murdered journalist, a glorified crime boss, and a rapper playing icon with a body count looming behind him, silence isn’t neutrality. It’s complicity.

This isn’t about “canceling” Oruam. It’s about being honest about what we’re consuming and who gets to be elevated without scrutiny. It’s about asking why Western media loves violent aestheticism in Black and brown bodies, as long as the violence stays abstract.

Oruam’s cover is striking. His story is not just provocative, it’s deeply political. If Dazed wanted to platform him, the least they could’ve done was tell the truth about who he is. Otherwise, it’s not storytelling. It’s laundering.

And that’s the context behind the content.

I feel PHYSICALLY SICK. My first thought was 'the sins of the fathers shall not be visited upon the sons' - but he has totally cancelled that free pass for himself.

Thank you for this. I initially reposted the cover on my ig account because I loved the aesthetics but upon reading your tweets and newsletter I removed it immediately after. Great journalism remains essential